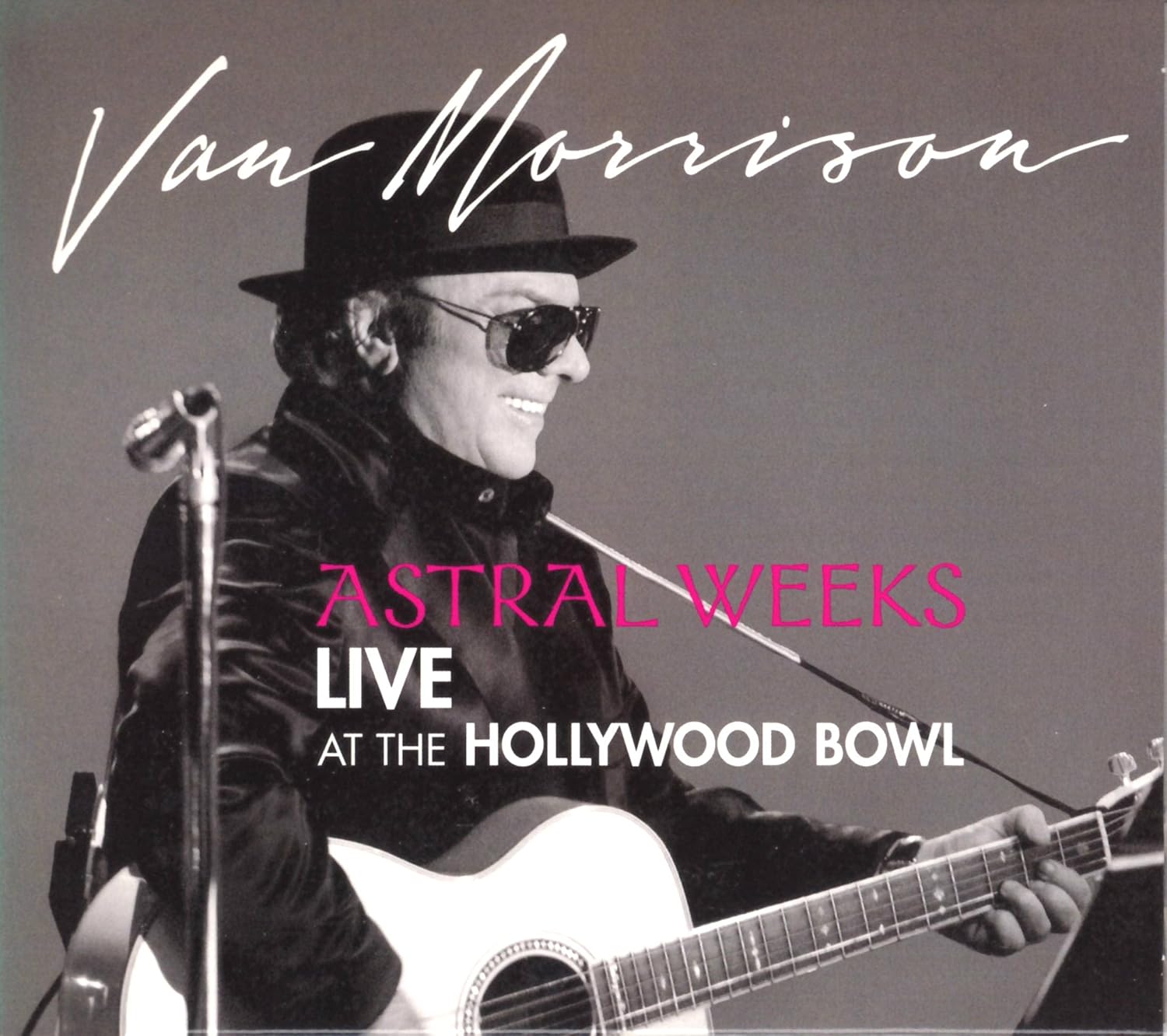

Belfast’s beloved son Van Morrison has been a recording artist longer than I’ve been alive. Them’s first, and penultimate, album—having dropped in ’65—preceded me by a full year. This is to say that the mystic blues shouter has always been around as far as I’m concerned.

Growing up on AM radio, Dr. Don Rose on San Francisco’s KFRC must have introduced the first Morrison classic I fell in love with, probably 1970’s Domino from His Band and the Street Choir, still one of my all-time favorite records.

Although our childhoods were separated by a good 21 years and the Atlantic Ocean, I have to think of him as a soul brother equally steeped in Blues and R&B from our respective impressionable ages. My father used to sit me down, when he wasn’t blaring Fats Domino or Little Richard’s Specialty catalog as loud as it would go, and explain what the drummers on Count Basie and Duke Ellington’s seminal First Time! The Count Meets The Duke were doing before continuing his ongoing dissertation on Jimmy Reed’s Live at Carnegie Hall.

As a result of what the less-enlightened among us might consider prolonged polyrhythmic brainwashing, I have often felt that perhaps I was grown in a weird sonic test tube to be a Van Morrison fan. The way that our man can stretch a phrase so that it lands off the beat like a jazz singer, or drop into a shamanic trance state to rival John Lee Hooker, it was a language I was well familiar with by the time he began to eschew the easy radio hit.

I can still remember watching Van Morrison: The Concert on PBS late one night in 1990. I think I was half paying attention, digging the traditional Irish songs that had been on his collaboration with the Chieftains a couple of years previous. A good hour into it, the band broke into In the Garden from 1986’s No Guru, No Method, No Teacher at a frenetic pace. My first thought was that they were disrespecting the elegiac beauty of the song, a meditative highlight of the album.

And then, with the crack of a snare drum, as suddenly as we were launched into the firmament by the upward thrust of the band, we break gravity and jettison the boosters. Van touches the seventh verse (so lightly) and then slips into a gravity-free trance, repeating, “You fell, you fell, you fell,” tasting and twisting both syllables, recasting them, rejecting them, pacing the stage like a nervous panther in a cage, and finally placing them, “from the garden.” I remember walking toward the TV, and saying out loud, “What the fuck?”

I had seen plenty of live music by then, but I had never seen someone so enraptured by the moment, in the moment, of the moment. And who the hell is he talking about? Is he singing to mankind or speaking to the angels that were cast out of heaven? Maybe he doesn’t even know. Maybe it doesn’t even matter. It’s fucking poetry, it is.

That song still makes me tear up every time I hear and I don’t know why. Is there a primal longing to return to the proverbial garden that Morrison tapped into? I am sure that he would just remark, as he has many times, “It’s just a song. I’m just a songwriter.” I call bullshit, but OK, I get it. The creative arts, when one is open and lucky, exist in a realm of real magic. It is best not to piss off the muse by calling it out.

I have always respected Morrison’s high regard of the muse and his willingness to follow it wherever it might lead. The two records he produced during the COVID pandemic, and subsequent lockdown, gave his critics plenty of raw meat to devour. However, after a good 60 years in a game he, himself, has eschewed in both in song and action, I felt, and still feel, that the man has well earned the right to respond to societal events however he might feel appropriate.

One can’t be surprised that an artist who sang the following, nearly 55 years ago, might not give a shit what anyone has to say about his business one way or another: Don’t wannna discuss it / Think it’s time for a change / You may get disgusted / Start thinkin’ that I’m strange / In that case I’ll go underground / Get some / Heavy rest / Never have to worry / About what is worst or what is best

A re-entrenchment along the lines of Bob Dylan’s two solo folk records of 1992–93, seem to have redirected Morrison’s inspiration. 2023’s Moving on Skiffle revisited the type of music he played in his youth, before the trap and trappings of fame; whereas Accentuate the Positive, from the same year, celebrated rock & roll at it’s earliest, and least calcified, incarnation.

This summer’s Remembering Now reads at first as an aural CV of all of the genres that Morrison has explored over the years, with familiar places and themes bubbling up in the fragrant stew. The closest cousin in the Man’s deep catalog sounds to be 1991’s Hymns to the Silence, one of my all-time favorites.

Eighty years on, Morrison’s voice sounds as strong as ever; age bringing, if anything, a resonance that was missing in the early days. Listening back, I hear the young, brash rocker of 1965–66 as a trumpet, blasting out the theme over the roar of the band, announcing the new world as it was unrolled before it. These days, Morrison’s instrument has become a tenor sax, deep and luxurious, able to evoke longing and defiance with equal strength and intention.

Roll me over, Romeo.