Scanning the used books over at the wonderful Book Passage in Corte Madera, I came across several faded paperbacks by Beat writer Lew Welch. One of the lesser-known Beats, Welch is probably best known as the other hopeless drunk in Jack Kerouac’s majestically depressing Big Sur.

Flipping through his work, however, I found Welch to be a gifted poet with a value system more in line with the nascent hippie movement that was emerging in the mid-to-late-’60s. That Welch disappeared into the woods around Nevada City with his 30-30 after writing a goodbye note only adds to the mystery of this important writer I had somehow missed during my fascination with all things Beat.

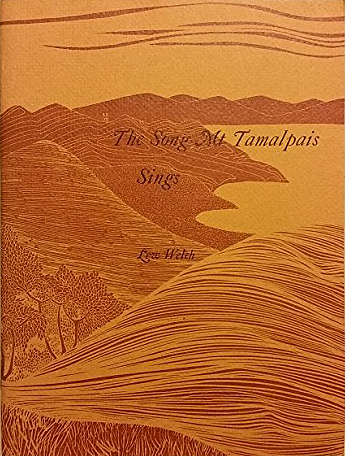

Welch’s brief, lyrical chapbook The Song Mt. Tamalpais Sings, originally published in 1969, and reprinted with three additional poems by Berkeley’s Sand Dollar in 1970, features a stunning wrap-around scratch board illustration of the Marin Headlands with a slightly more provincial San Francisco peeking (peaking?) over the hills.

The title poem, the first in a pair of bookends that feature the mountain, intones the mantra: This is the last Place. There is nowhere else to go, as Welch boils down the western movement of humankind. Centuries and hordes of us, from every quarter of the earth, now piling up, and each wave going back to get some more. Buddy, you have no idea.

The last poem, Song of the Turkey Buzzard, looks deeper into a riddle posed in a triptych of Zen-like koans (complete with commentary by Welsh’s literary alter−ego, the Red Monk): If you spend as much time on the Mountain as you should, She will always give you a Sentient Being to ride… What do you ride? (There is one right answer for every person, and only that person can really know what it is)

Of course Welch, like anyone would, wishes for a cool totem animal like a mountain lion, but the mountain has other ideas: Praises, Tamalpais, Perfect in Wisdom and Beauty, She of the Wheeling Birds. Throughout the course of the poem, the mountain throws some pretty clear hints at him until in the second canto, he finally acquiesces, and given his final act two scant years later, it begs one to wonder if he hadn’t been planning it all along.

With proper ceremony disembowel what I no longer need, that it might more quickly rot and tempt my new form NOT THE BRONZE CASKET BUT THE BRAZEN WING SOARING FOREVER ABOVE THEE O PERFECT O SWEETEST WATER O GLORIOUS WHEELING BIRD